By Matthew Devine

4237.175 TSE, 0735 LRT

Commander Honeycutt lay on the lumpy floor of his prefab, stretching. Wind warped the plastifoam walls, and the lightweight canvas ply roof thumped rhythmically against the support struts. As it had done all night. He had not slept well in days, and his face looked haggard even to him. After the bed deflated and retracted, he shaved, dressed, and stood in the center of his command center that had been unfolded on a plot of soil four square.

“Enable lighting profile. Enable environmental acoustic dampening,” Honeycutt said. Interior lights intensified and followed him as he reached for his term screen set on a table that unfolded from the wall.

“Open V-LOG, timestamp, and tag location.” Honeycutt called into the empty room and began scrolling along several feeds on his screen. “Commander Honeycutt, Expeditionary Force 457. Planet Mercy Seven, site seven, day three. Reference coordinates in mission brief. Sync log on scheduled interval or upon closure. Break.”

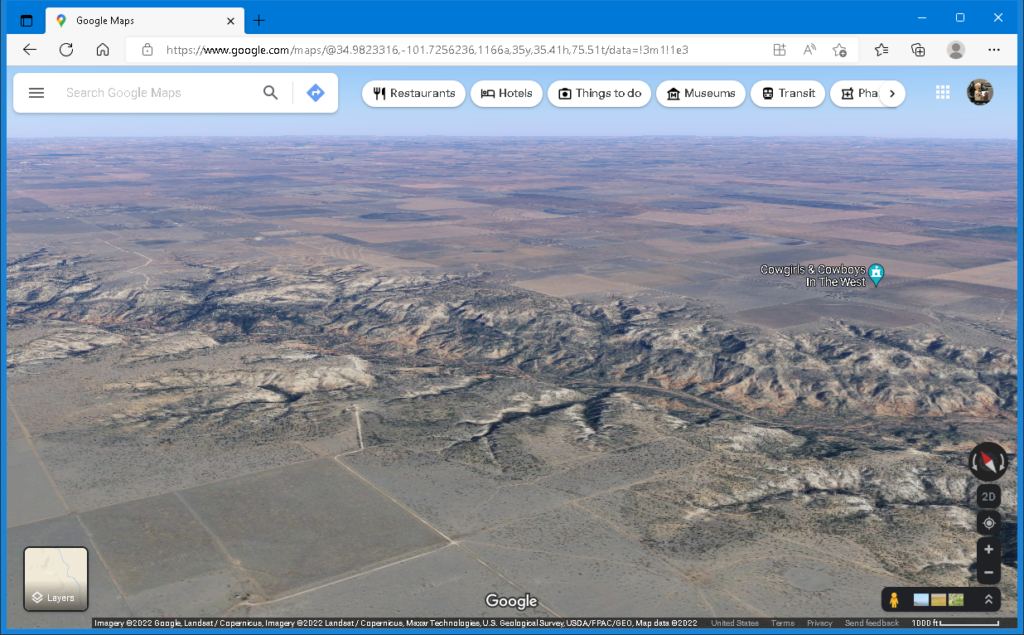

Why was this so difficult? On Honeycutt’s table, A motograph of Maire smiled, blew a kiss, and twirled in her white dress. The images had been captured on their wedding day, when they had married aboard Copernicus five years ago, but the backdrop was a spliced image of snow-capped mountains from earth.

“Open comm to Ecology,” Honeycutt said.

Sargent Nixx answered. “Reporting, sir. One moment, please.”

Honeycutt lay the motograph frame on its face, and a hologram emerged, Maire, dancing on the back. He switched it off.

When visual communication was established, a hasty, lumpy ponytail swished over Nixx’s shoulder. She wore a wrinkled, faded blue jumpsuit. Her smile was almost contagious.

“Reporting, sir,” Nixx repeated, her voice giddy.

“Is there a chance you have something other than amino paste for breakfast?”

“Negative sir, but I have not completed all my analyses yet. Site three will have a season of grain and had several endemic tubers that could be cultured. K-value was over eleven-three! I still cannot believe we are standing on a T-Type planet.”

“It does not seem real,” Honeycutt said. “Sargent Winters?” Honeycutt asked, Nixx blushed.

“Reporting, sir.” He emerged from the lenticular shadow in one corner of Nixx’s prefab and slid next to her awkwardly, the distance between them, forced. He had missed a button on his own rumpled jumpsuit.

“Since you must be helping Nixx with her reports, I take it the seismology evaluations are complete?” Honeycutt asked; they both squirmed.

“Negative sir. I am a day behind. The plasma corer broke again, and my team is working with tech to repair it. Moisture is such a problem. We expect to position it this afternoon and nurse it through the evening. I expect to be back on track tomorrow.”

“Preliminaries?” Honeycutt asked. Nixx and Winters glanced toward each other.

“I expect an overall K-value of this site—adjusted—between four and five,” Nixx reached for her pad. “Closer to four. It will support a very low-density population.” Nixx glanced toward Winters.

“But the views are staggering,” Winters said. “We’ve only scratched the surface…”

“You’ve mentioned already,” Nixx chided with a grin.

Unprofessionalism ran rampant among Honeycutt’s crew since the discovery, but he resolved to address it only if it became a problem. Members of his expedition were the first to set foot on active soil. No other living human had smelled mold or had tasted unrecycled water. They were the first in many generations to see vistas unhindered by the visor of an exo.

Winters nearly suppressed a smile and continued. “My team has never seen so many rocks. We are experts regarding a thing we’ve never truly studied. Before Mercy Seven, we’ve only seen fist-sized chunks retrieved by a sampler, and those had already eroded countless times by uncertain processes. Boulders. Mountains. I have a fine team, but they can get distracted.”

Yes, the entire chain of command was distracted, and Honeycutt was not immune.

“Astro was finished a decade before we arrived, Atmo is complete except for monitoring, and Ecology is on target. Winters, I need to know we are not sitting on a planetary cataclysm when I submit my report. Honeycutt over.” The image projected on the wall disappeared.

Honeycutt turned the motograph on; his holographic wife danced for a cycle, and he turned it off again.

“V-LOG resume. I have approved FTL transfer of the cargo pod aboard Copernicus to site seven of Mercy Seven. I spent my entire commission to fund the delivery, and I will probably die a pauper. But I filled my lungs with planetary air. Only members of expedition 457 can boast of that. Break”

Honeycutt donned thermals, put on his boots, and stepped outside in the morning chill. He held his breath. Temperature variance aboard his craft indicated a potentially catastrophic system failure; the substance of nightmares. The next generation would adapt to a variable climate naturally, and maybe in time he would too.

He walked across the rocky terrain, kicking stones ahead of him. Some were darker, some had streaks. Limestone, Winters had said. It was all so foreign to Honeycutt too. A plant with rigid leaves ended in barbs; clumps of brittle, brown, fine-bladed vegetation were immediately recognizable as grass, like some of the hydroponic produce aboard Copernicus. Nixx saw miracles of life and taxonomic relationships; Honeycutt saw extremes.

Arriving at the nearest atmo station, he checked power and communication functions, and continued walking along the rim of the basin wherein they had raised their prefab camp.

What would Maire think of this planet? She loved people. She was not a collector of prizes. Would she be inspired by the scent of rain? Or the dust and sun that scoured unprotected skin? He did not think so.

He checked the other atmo stations set up around their camp before returning to his prefab.

“V-LOG resume. I have petitioned the council to name this planet. Certainly, a million others have done so as well, but as commander of the discovery expedition, mine should be among the first. And I am commander—perhaps that lends weight. However, I am not a politician. I am impoverished even among the destitute if that ever meant anything.”

Honeycutt turned on the motograph. Maire blew him a kiss and danced. Math involving distances was difficult, but he had performed the calculations by hand the moment his expedition had arrived. She was nearly two centuries old now. She would be the first in many generations to be buried beneath soil, among the majestic peaks of a habitable planet that would hopefully bear her name.

“Break.”