By Matthew Devine

Magic entered the world and violently marked the landscape. Not only did the elders tell the tales to children as they sat around the fires at night, but some of the people could feel magic. A gentle tug, some claimed, an affinity for one of the primal humors. Those attuned to the humors knew.

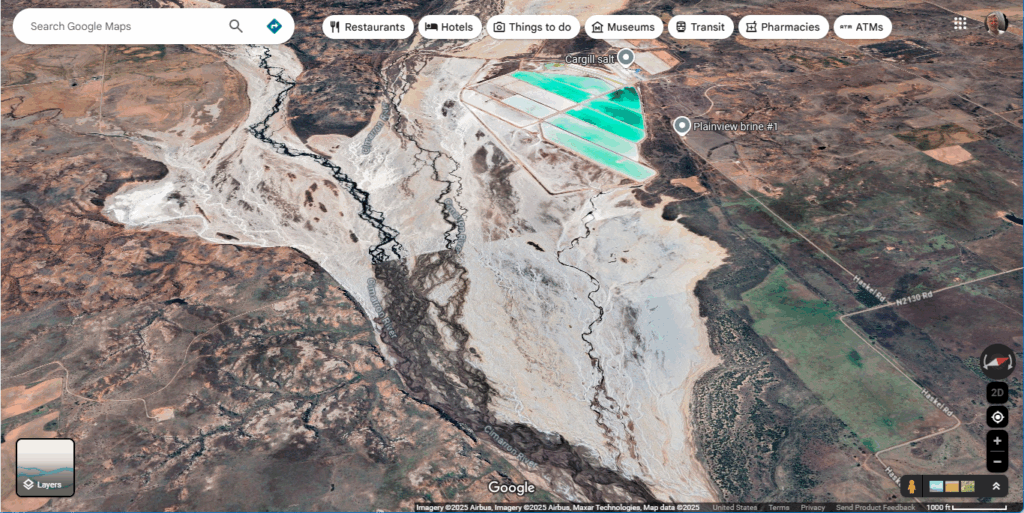

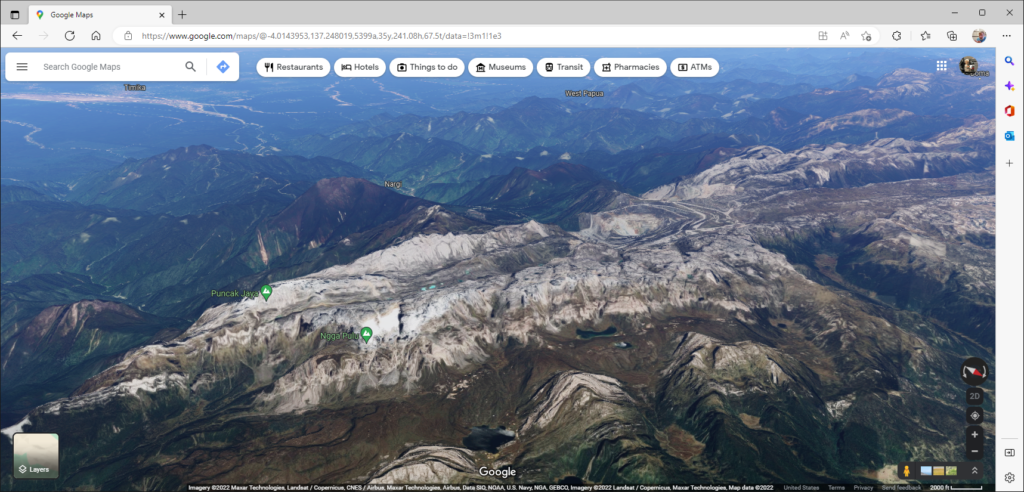

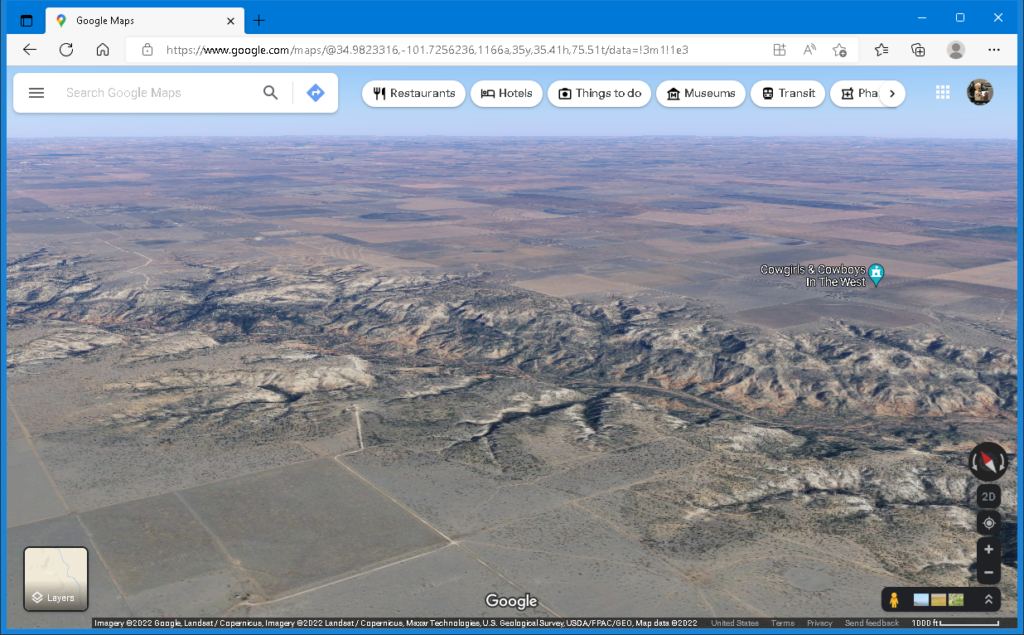

There once was a world, peaceful and serene, untainted by magic and spirits, but when they arrived, spirits of fire warred against spirits of water. Mountains were formed and canyons were carved. Spirits of air, quiet, patient, and invisible, did not get involved in the squabble, but they spirits were nonetheless involved in shaping the world. Together, these formed the primal humors of magic.

Jarek knew.

Some called it a blessing, some called it a curse, but there were only a few from the clan in each generation capable of feeling magic, and fewer still that could influence it. His great aunt had been one; a water witch, they called her. She could swim as fast a man could jog. But that was the extent of her ability. It was called a curse. Bree’nel the Sleeper had been dead for a decade, but he could cause clouds to form and make rain. Afterward, he slept for days at a time. It was called a blessing.

The attuned had a primary alignment to one of the humors, but they could feel others as well; Bree’nel knew air almost as intimately as he knew water, it was said. Jarek’s aunt spoke with familiarity of things under the land, and she could feel fire in unnatural ways. She spoke of nonsensical things too… ergo the curse.

Although in recent memory, people had been influenced by the gentle spirits of water, the stories recorded men who could immolate themselves at will or cause a fire to burn without spark, ember, or tinder: all demonstrations of a curse.

When a person died and the land received the dead, the tribe quickly moved on, carrying the memories of the deceased with them, and nothing else. Too many dead in one place could anger the land again and provoke the spirit of death.

“Aunt Tikka was not crazy,” Jarek said. He shifted his pack and continued walking uphill.

“Like hell she was. You didn’t know her.” His father mumbled behind him. “Elders told the story of the moon on the eve of the hunt, and she corrected them. You don’t interrupt the stories, and you don’t corrupt them. She knew better; she was crazy. And you never heard her talking about switching places with her shadow.”

Jarek had visions of a land with an orange sun; dimmer, larger, and well… plain different. Plants were huge and their leaves so dark a green as to be almost black, absorbing every ounce of light that might otherwise reach the ground. Was he crazy too?

Father continued. “When she realized it, she stopped acting out, stopped saying crazy things. But you don’t forget that stuff.” The shuffle behind Jarek stopped. “You don’t see unnatural things, do you, son?”

Jarek turned around. “Of course not,” he said.

“Then why are you dragging me up this mountain? There were sheep and deer on other mountains close to camp. We’ve been traveling for days, I’m tired, and I know you better than that. You are following a pull.” Father kicked rocks aside and sat on the hillside.

Jarek sat next to him, opened his pack, and handed his father a slab of dried venison before drinking from his own waterskin.

Father nodded his thanks. “You think me a daft old man. You’ve planned for weeks, I watched you.” He chewed venison, staring at Jarek.

Where water flowed powerfully, the humors were stronger. Waterfalls, where the river bent, and where it tumbled powerfully over rocks; Tika had said so, and Jarek had felt it for himself, though he was not attuned to water. He also knew when he approached forgotten, ancient graves, but he told no one; the stories of necromancers were so grim, they were only told to older children and never at night. He felt a low, distant rumble, a churn like a snoring old man sleeping nearby belonging to the dormant but explosive spirits of the mountains, or so the stories told. There were places in the forest where vegetation grew dense and the humors healed both body and mind, albeit slowly. There were stories of healers with abilities beyond herbalists, healers attuned to life who could even regrow limbs.

Even if people were not attuned to humors, they could still see the evidence of old magic on the land.

“You feel a pull too,” Jarek said, his father shook his head.

“Tonight is a full moon,” the old man replied. “Am I going to be surprised?” He lay down, closing his eyes.

“You feel it,” Jarek insisted. “We can’t rest yet.”

The big humors were easily visible: fire, water, and air, mountains, rivers, and windswept landscapes. Many lesser humors existed, so abstract that they were unknown; the humors of life and death being the only exception. Tikka’s shadows had been a vesture of a lesser humor, Jarek’s visions were likely another.

“I’ve seen crazy,son. I’ll tell your story when I return home.”

“That’s comforting,” Jarek replied dismissively. He extended his hands and helped his father up. Both men groaned.They settled their gear and continued up the slope of the barren mountain.

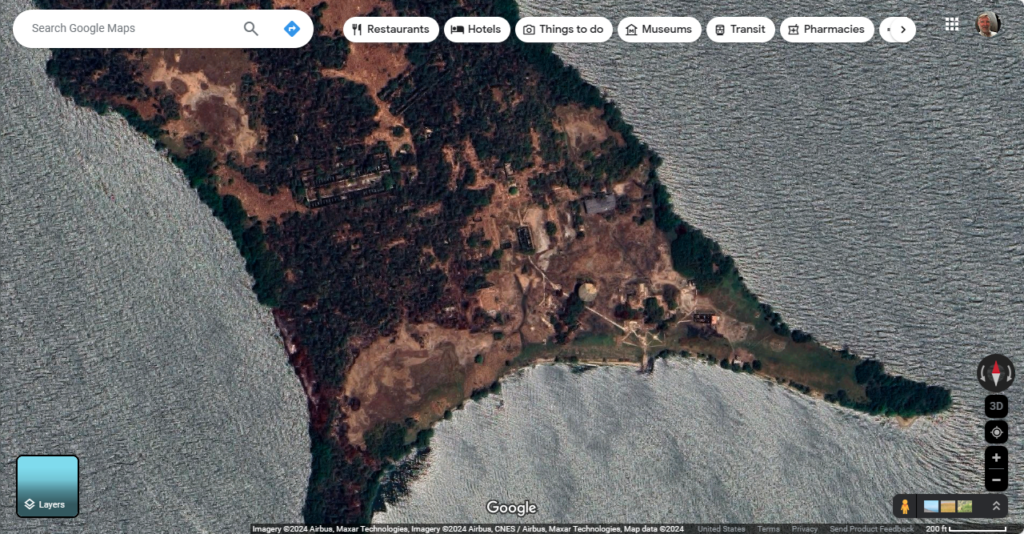

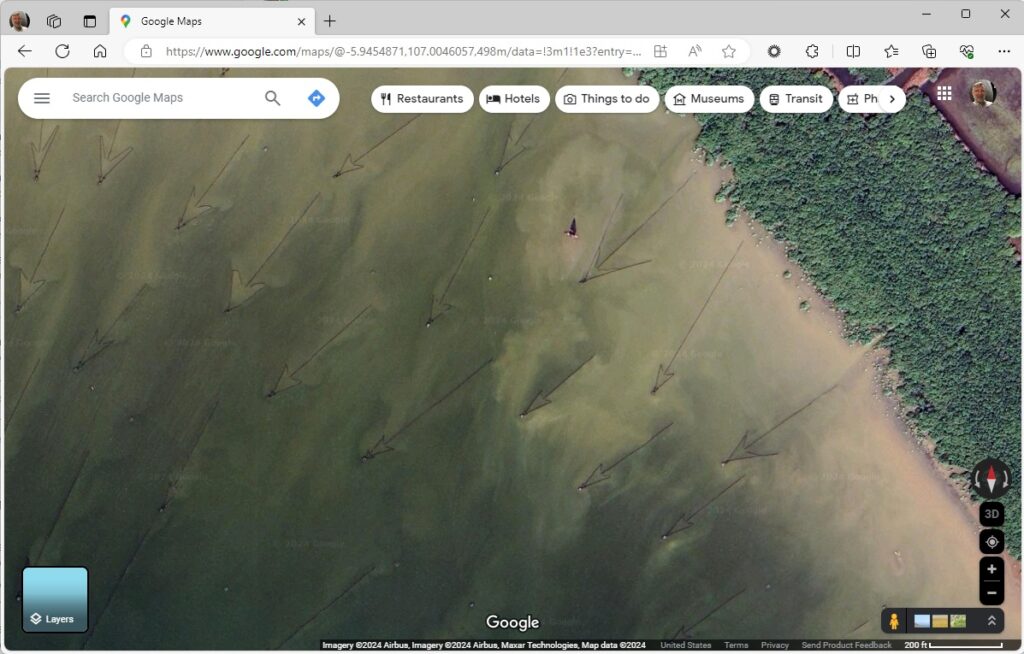

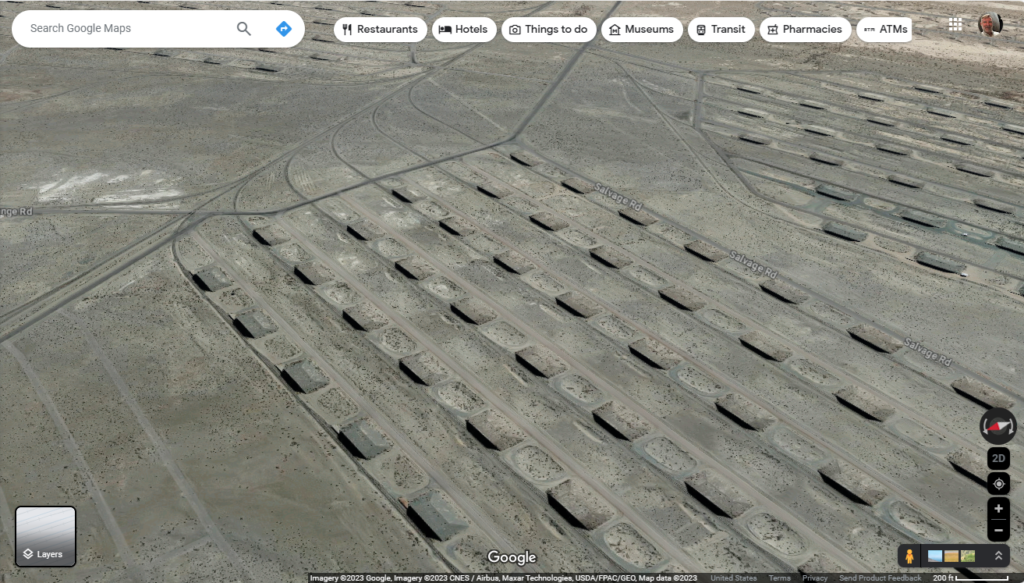

The pull was strong, irresistible. Jarek was certain his father was sensitive; the nearer they were to the source, the more energy both men had. Toward evening, Jarek reached the scar on the land; it had been summoning him for months. If Jarek could fly, from above the valley, the scar would look like a pile of rocks in the center of a spiral path made from the same stone; a continuous, arcing path radiating outward with unnatural symmetry and precision. Beneath the soil, the spiral continued—hidden—some distance from the pile. Jarek could feel where it began far from the central pile of stones, and he walked to the edge of the spiral, careful not to tread in the invisible troughs; only on the buried stone path.

“Jarek? What is it?” Jarek’s father stood, mouth open, silhouetted against the rising moon.

Jarek didn’t answer. He ran. Feeling the pull of the stones beneath the soil, he ran along the buried path. He continued to run along the path as it rose from the soil, following the spiral to the central pile of rocks. It was still distant, and the spiral path was long. It never crossed his mind to jump across the troughs, to take a shortcut to the center.

“Jarek!” his father called from outside the buried path.

Another step. Behind Jarek’s father, the moon turned orange. It was large and bright. When Jarek touched the central pile of stones, it changed subtly. The rocks became sharper, the path taller and completely revealed to him, and just beyond the spiraled path, dense green vegetation grew in the moonlight where his father had once stood.