Salt. In Central Oklahoma. Why?

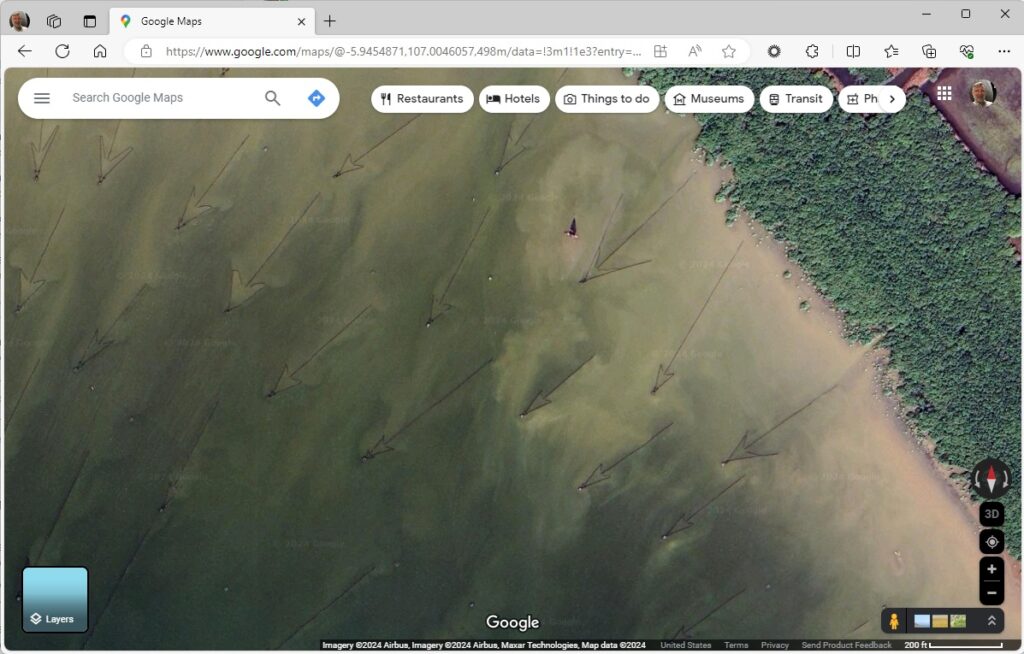

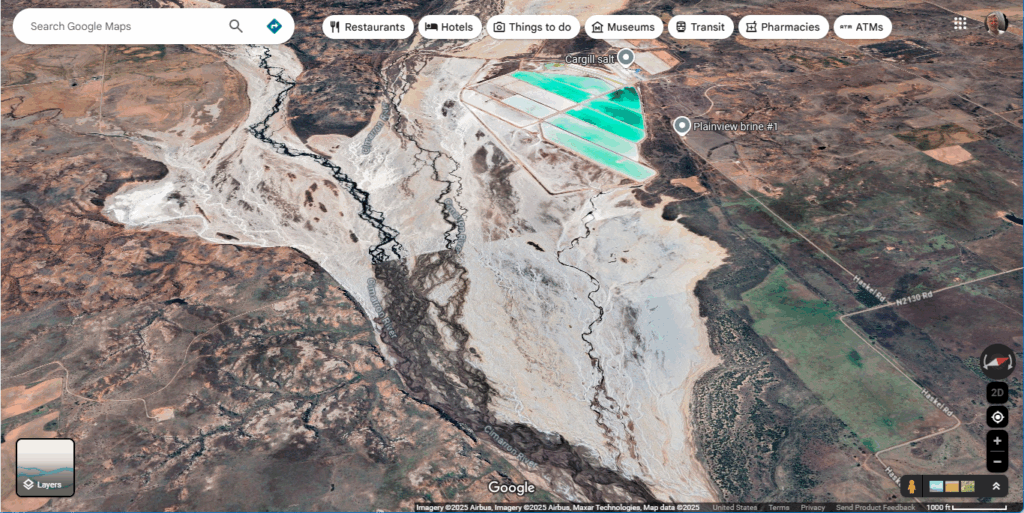

Geography, of course. And geology too. The Permian Basin is a geologic structure in New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas that has sequestered a bunch of salt which dissolves with rainfall and flows out out to the ocean. Here is a place where the river slows down and more evaporation (aided by an arid climate and a hot summer sun) occurs than it might otherwise do in other reaches of the river. To me, the key here is the braided channel in the middle of the image. When the floodplain widens and has very little change in elevation, the channel will silt up, and move around. More water flows through shallower channels and is withdrawn through evaporative processes, but the salt remains.

Also in this picture, a clever person has made a dam and pumps water into shallow ponds and allows it to evaporate, leaving the salt behind.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS FOR WORLD BUILDING? It’s how people will preserve meat. There’s a river, but the flow is slow and there won’t be rocks in the riverbed, but sand or silt. It’ll be hard to cross. The water will be poor quality, and possibly even unsafe to drink. Don’t expect there to be a lot of fish in this part of the river; any amphibians here will be highly adapted… or missing altogether. There is not a lot of rainfall here, so sunny skies, heat, and a late July traveler might arrive desiring nothing more than a sip of clear, cold water, which of course, will be denied.